“I thought I should ask the Vietnamese pilots…”

Interview with Istvan Toperczer

All those interested in military history, may know the name of Istvan Toperczer. Besides his articles published in various periodicals, he has written several books about the Vietnam conflict, to be more precise, about the air war over Vietnam. He was breaking fresh ground by publishing volumes focusing on the Vietnamese side in a topic so far presented more or less one-sided. Of course, to make all that come true, he had to use the most competent sources. So he travelled to Vietnam... Six times in two decades.

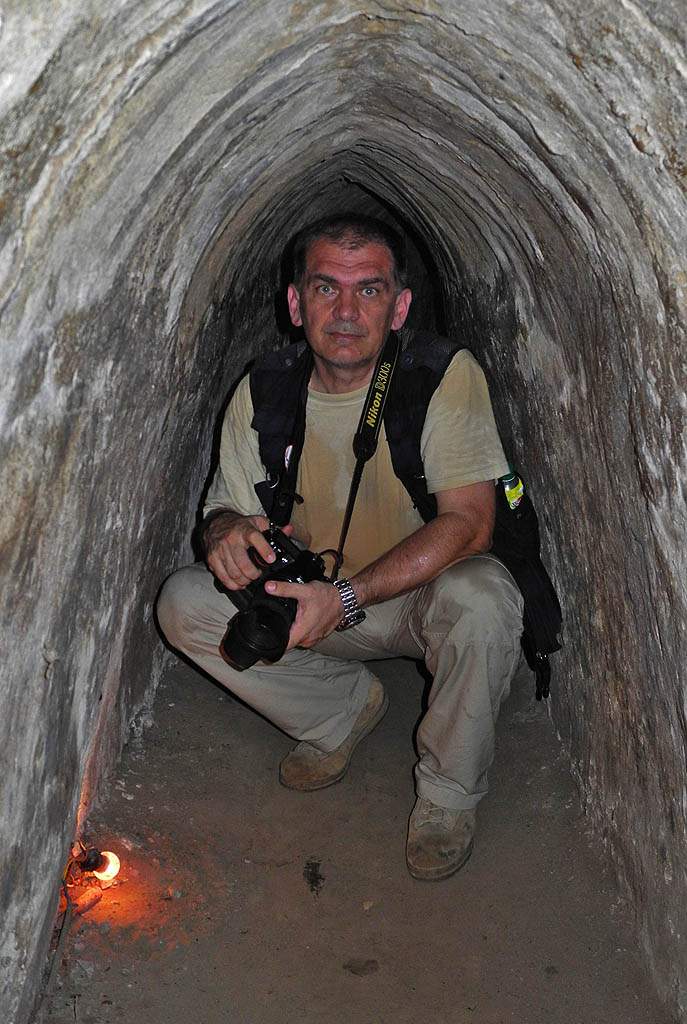

In the tunnels of Cu Chi

When did you travel to Vietnam for the first time?

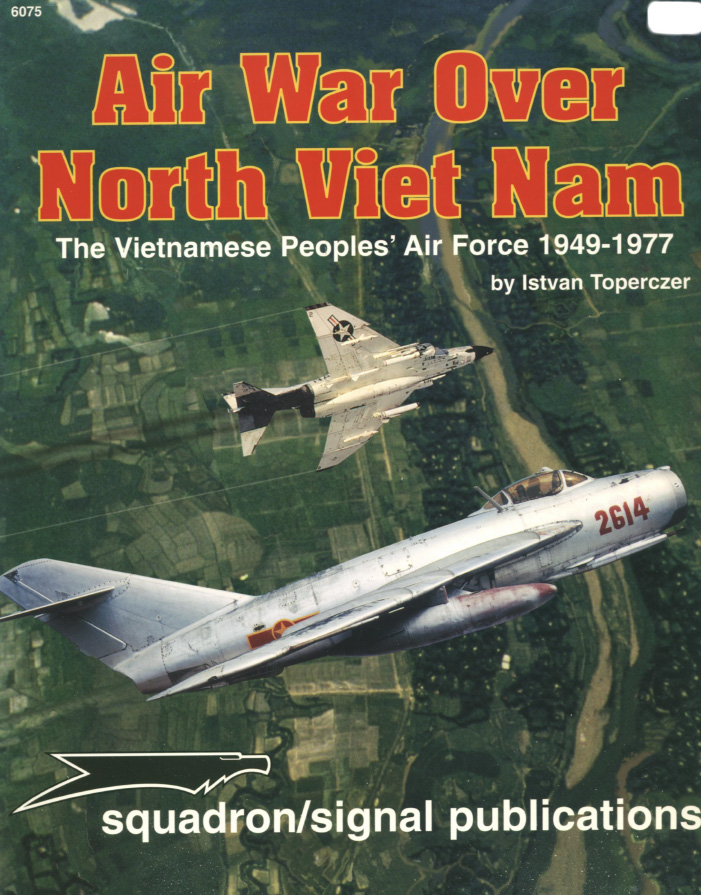

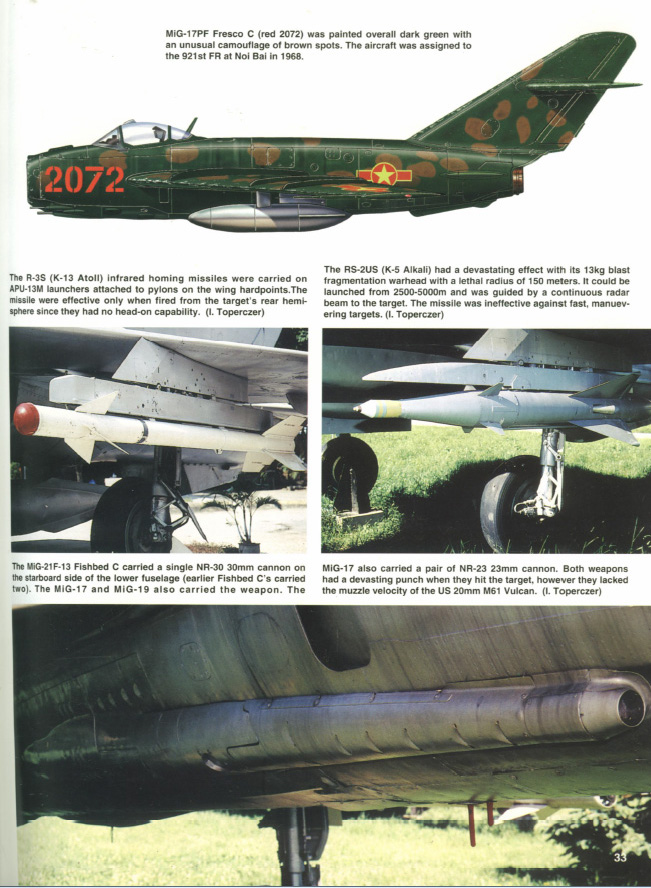

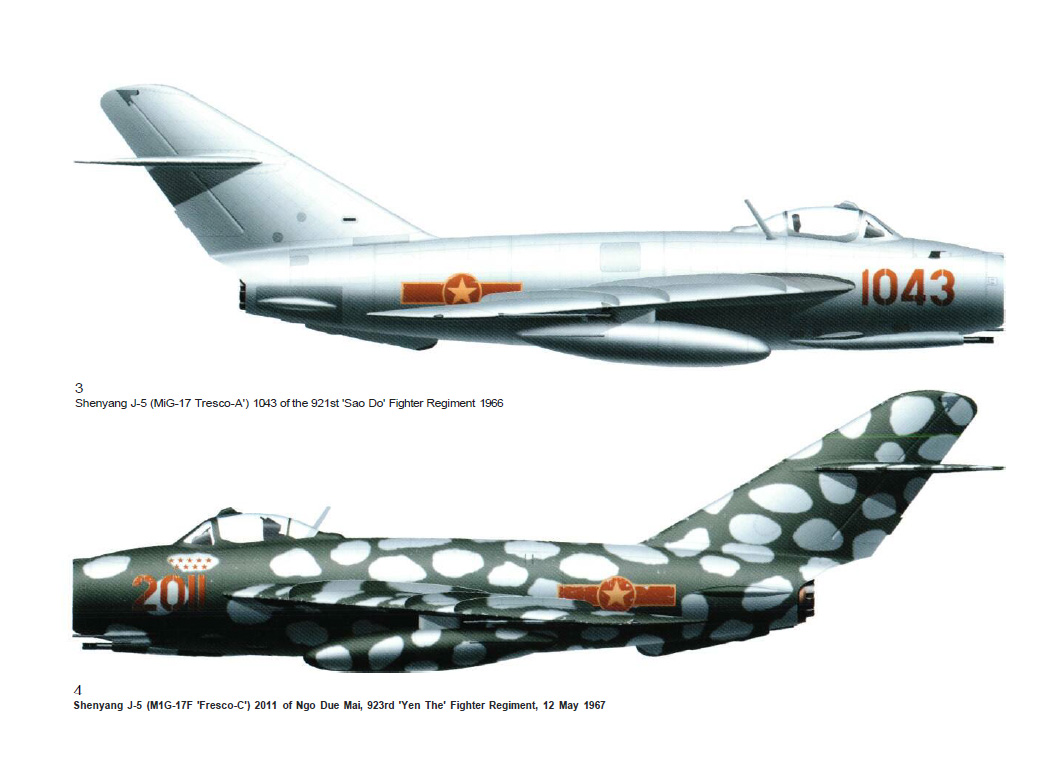

It was in 1994. Doi Moi – the "glasnost" of Vietnam – had taken place only one year earlier. It was not a change of régime as the régime remained: the change was rather economic. That involved an opening to the world. Via the Vietnamese Embassy and the Hungarian Ministry of Foreign Affairs I requested permission to present the Vietnamese side of the Vietnam air war, attend local museums, talk to pilots and do some research. It was granted, so I travelled. My first journey took a month. Those days we had much less printed sources, but you could find more photos in museums, with invaluable captions. What I collected then, went to the first volume, Air War Over North Vietnam, published by Squadron/Signal in 1998. In this book the list of aerial victories took only one A4 page.

But that was not your last journey or your last book...

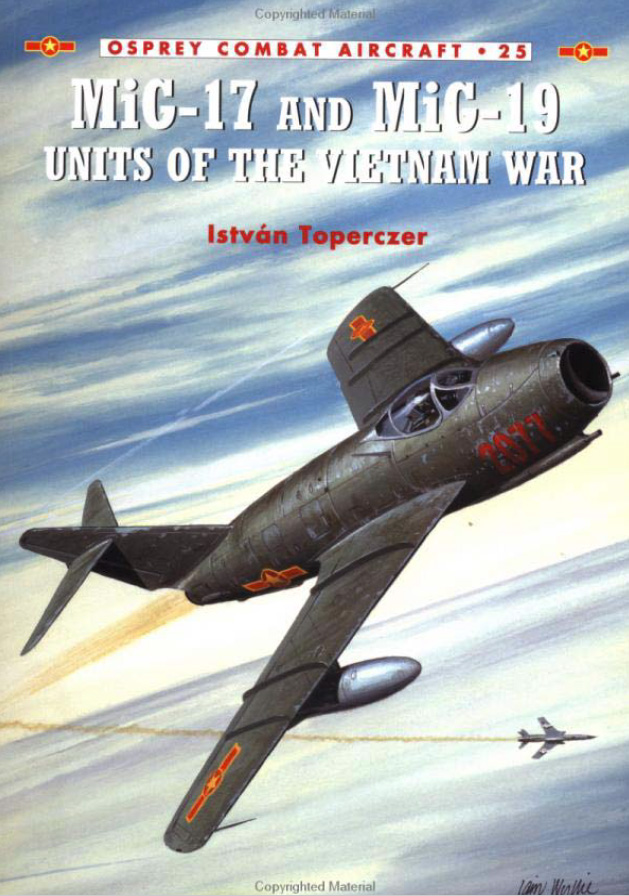

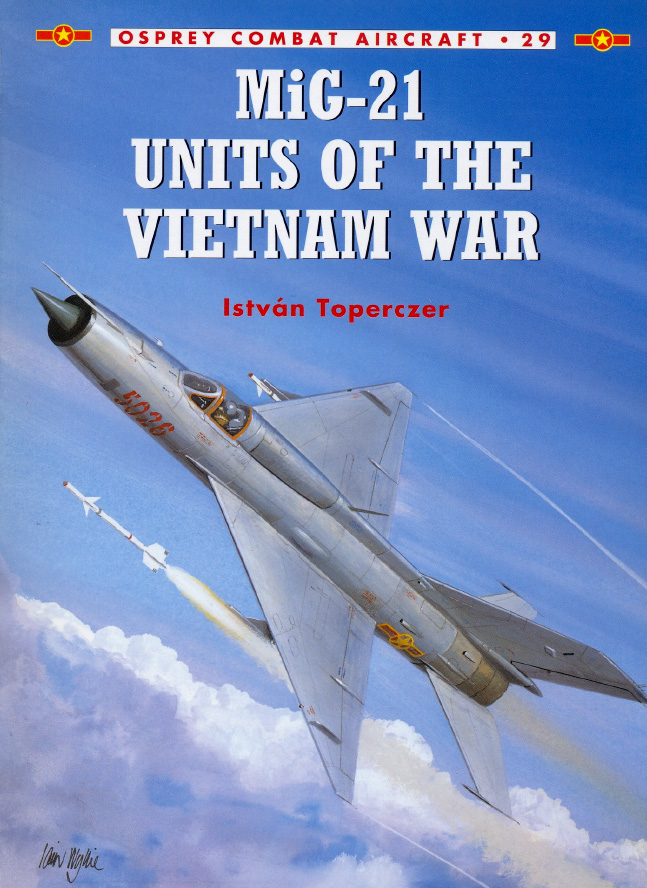

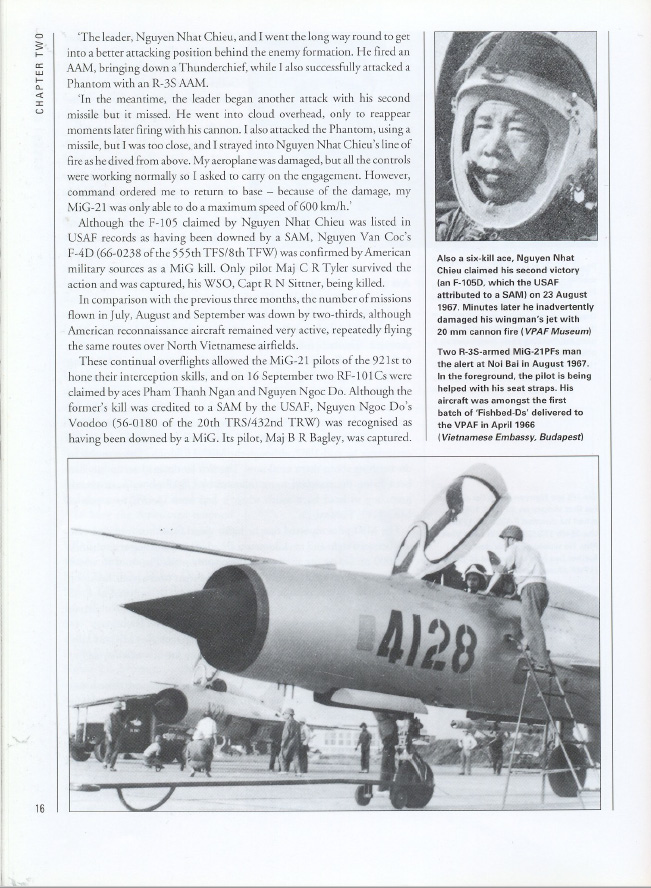

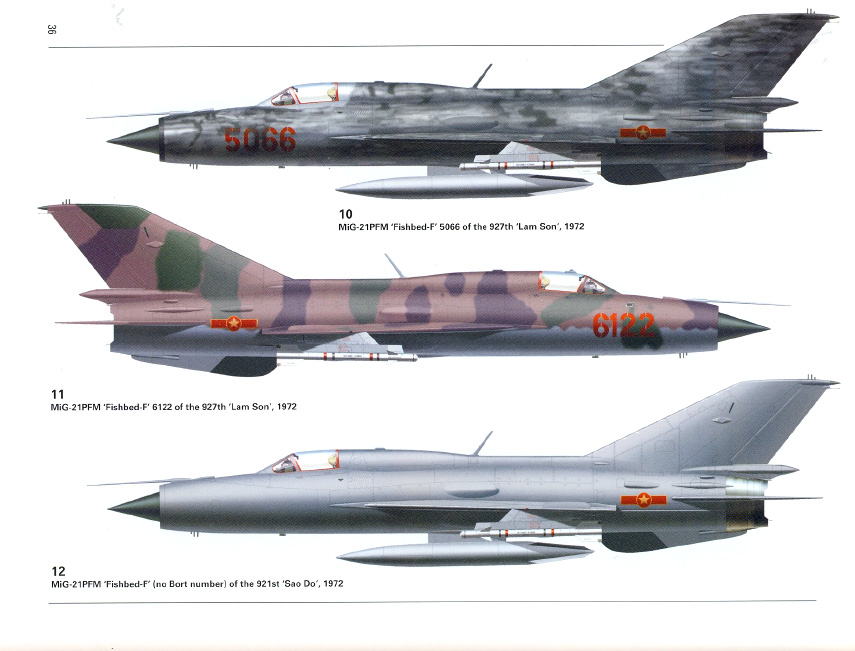

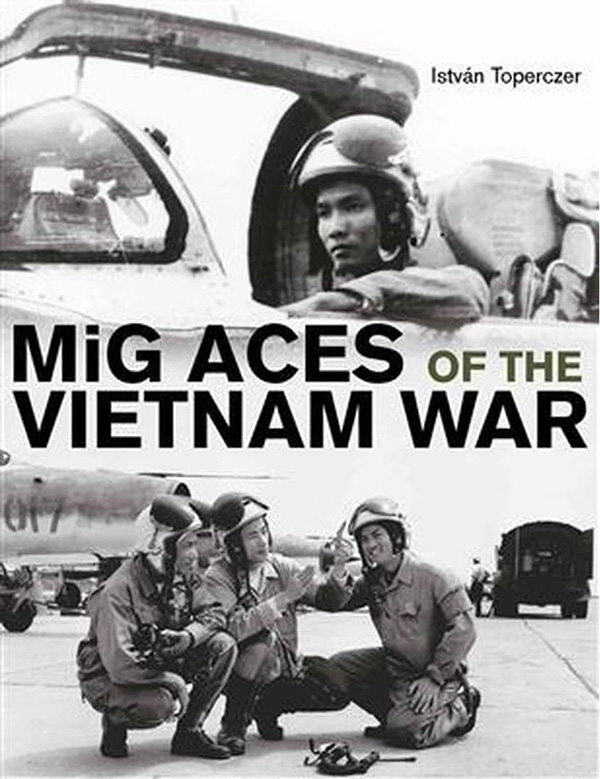

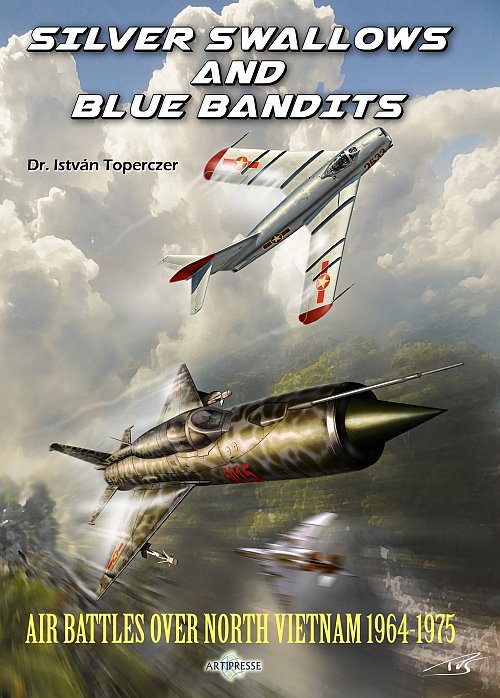

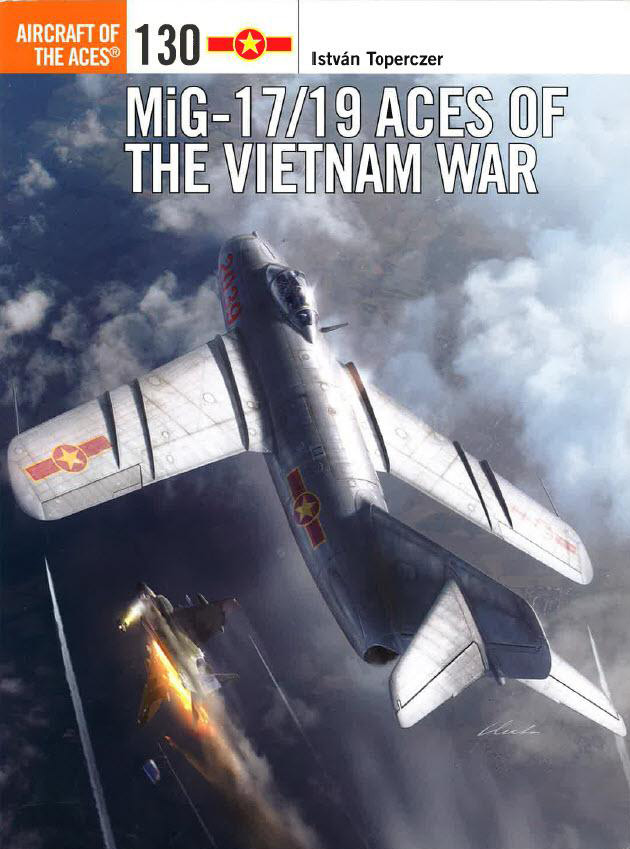

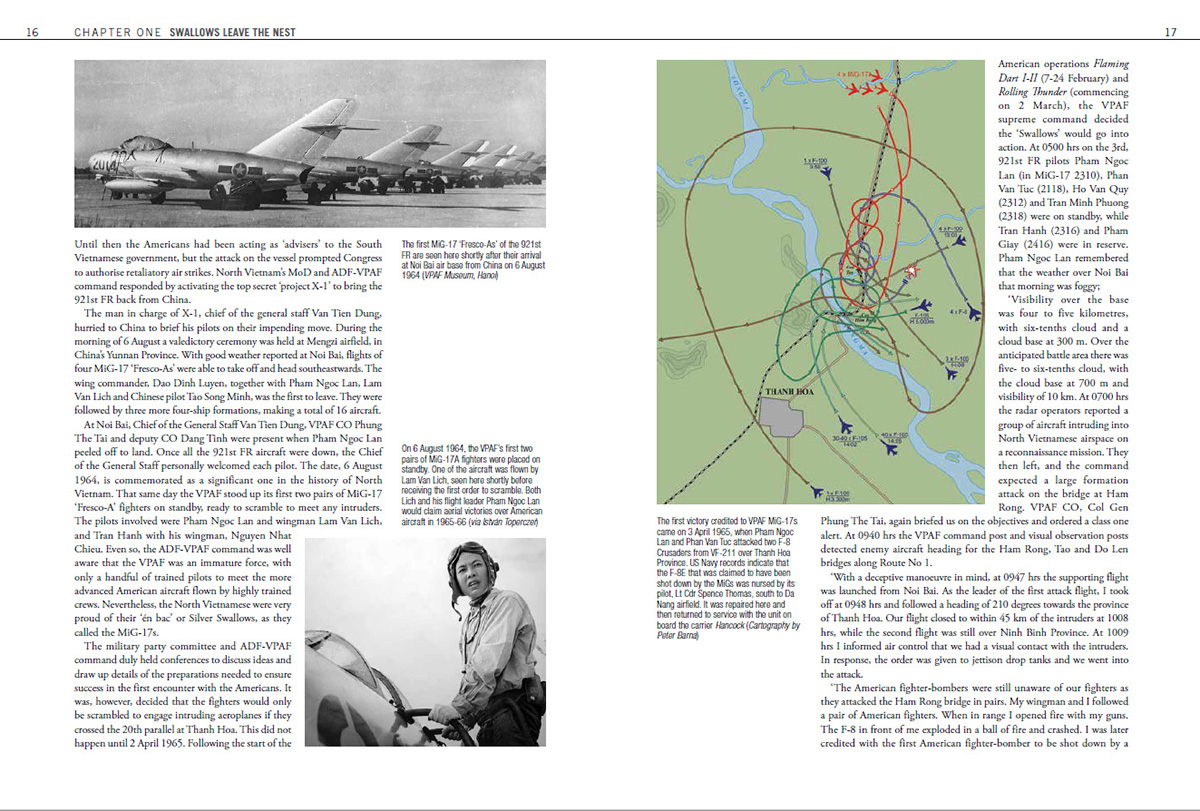

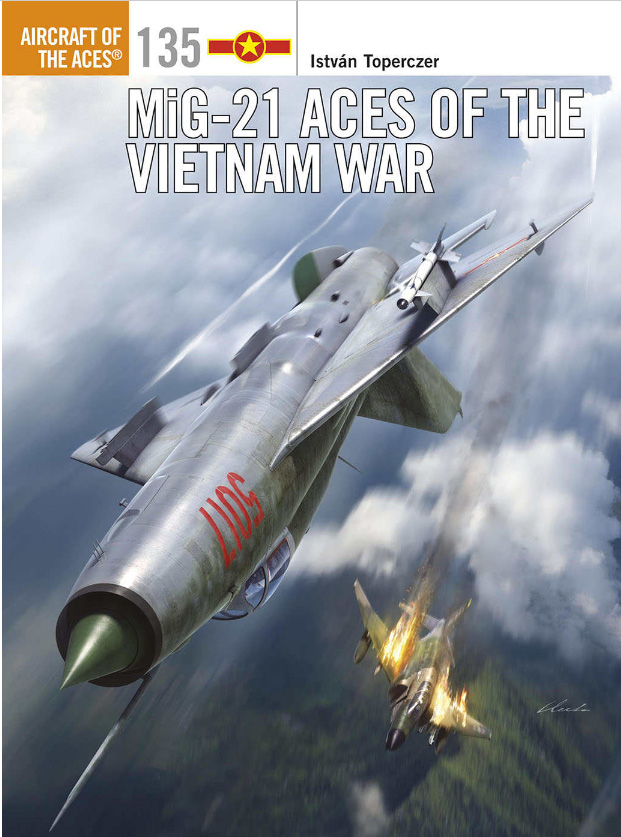

In 1997, then in 1999 I travelled to Vietnam again and accumulated more materials. In other words, when the first book was going to be published, I was on it, again. I contacted Osprey Publishing. They asked for a synopsis and some pictures – they already knew my name by the first book. The second book offered more, as several Vietnamese pilots had retired by then, and they were more open to speak. Plus I managed to find American pilots, too, and I persuaded some of them to talk about how they had been shot down. Having sent the whole manuscript, the Osprey guys said it was too long for one volume so I should expand it to make it two. That is how the titles MiG-17 and MiG-19 Units of The Vietnam War and MiG-21 Units of the Vietnam War came to being. These are about the Vietnamese fighter squadrons and their battles.

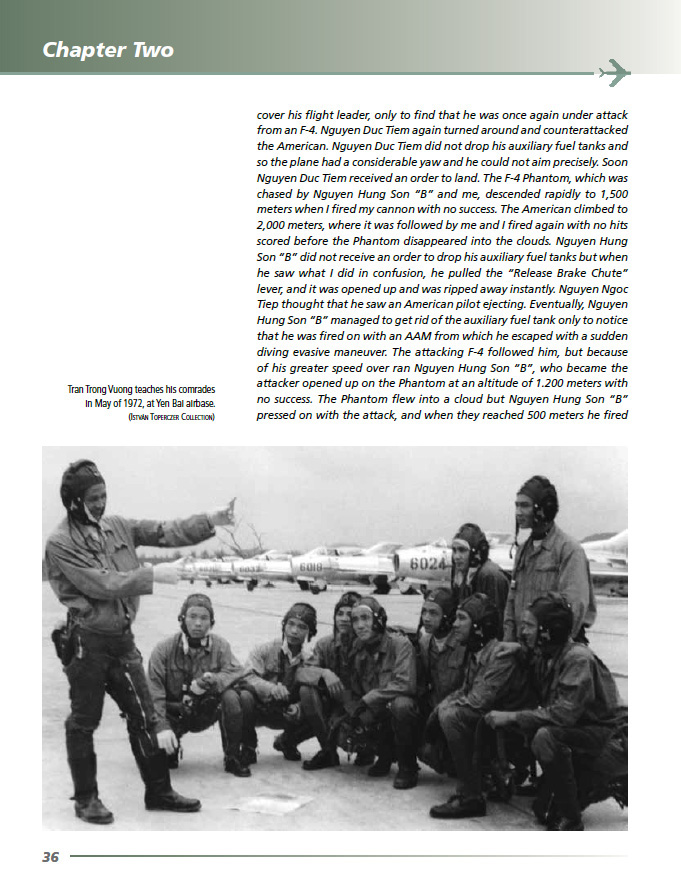

Nguyen Van Coc, top ace of the Vietnamese Air Force

recounting a dogfight

How did the aces come into view?

As years went by, more and more Vietnamese pilots retired and I thought I should ask them. A French publishing house, Artipresse asked me if I could make up a book based on the first three and all the new information gathered since. So I decided to travel again and continue. I flew to Vietnam in 2013 and I met numerous famous or ace pilots. I collected tons of info, in fact so much that it would be enough even for another book that concentrated on these aces. If you look into it, you can see, that the list of aerial victories takes more pages now...

In accordance with Doi Moi, more and more historical summaries of air squadrons were published in Vietnam from 2001. These were inside publications, not sold in bookshops, but they were not secret or confidential. I have a few, some of them in original, some of them in photocopied version. I have a Vietnamese friend for about 20 years now. He's been living in Budapest for a while, he studied here in the 1970s, his Hungarian is impeccable. He helped me a lot with translation, but I do understand a lot of the written text by now.

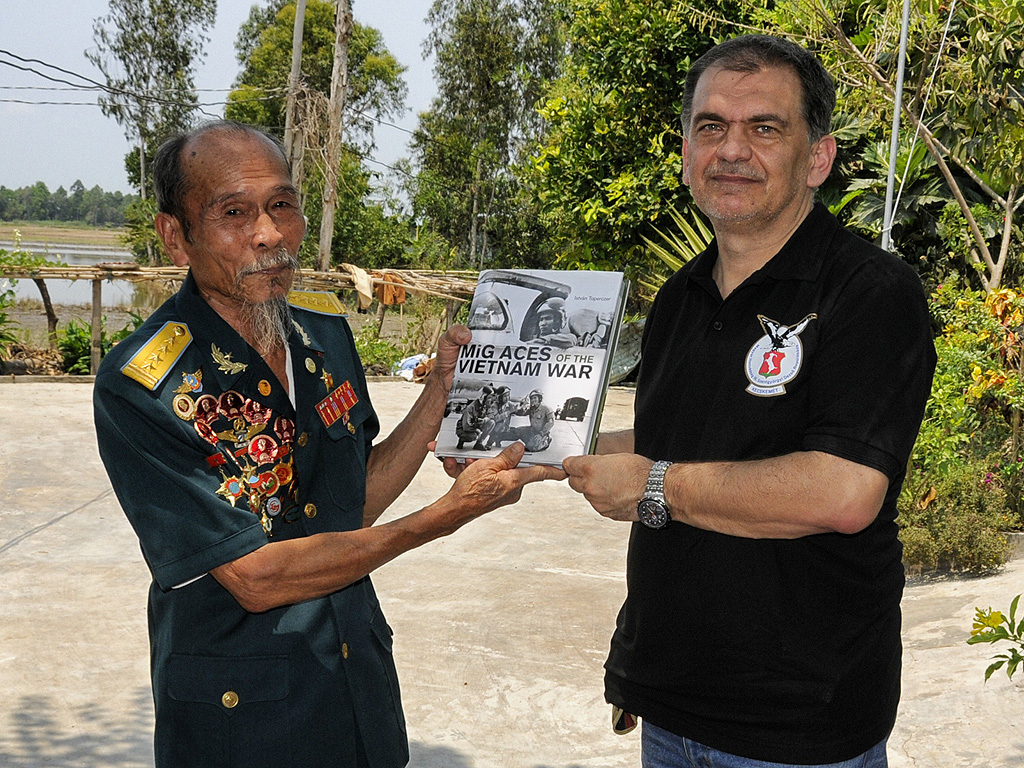

Nguyen Van Bay, MiG-17 ace pilot with 7 aerial victories

Two years after Artipresse published Silver Swallows and Blue Bandits and Schiffer released MiG Aces of The Vietnam War, Osprey asked me if I could write a book particularly about the MiG-17 and Mig-21 aces. It was an interesting proposition, so I travelled to Vietnam again in 2016. I talked to further pilots, collected written materials and found some new photographs. I knew that all these would be enough to produce completely new volumes. These books, MiG-17/19 Aces of The Vietnam War and MiG-21 Aces of The Vietnam War feature pictures 80-90% of which had been unpublished. I drew most of the graphics. For example, this is a diagram of a hangar complete with my own photographs taken on site. And I received some photos from Hungarian pilots, taken during their training in the Soviet Union, of the planes used both by Hungarian and Vietnamese pilot trainees. As for the MiG-21 book, I was told that they could not put all that in 96 pages, the standard spread. I explained them that descriptions of air combat and the duration of the air war could not be reduced. Finally, they provided some more pages and that is something they do not do very often. So this book is a bit thicker than the others.

How about Hungarian editions?

So few readers are interested here, in Hungary… Anyone really interested goes right away for the publications in English. I wrote a few articles to Aeromagazine, for instance about how the Vietnamese transported fighter planes from one base to another using helicopters or how Vietnamese AN-2 planes bombed the American flight control centre in Laos.

Do you have other plans?

There is not very much left to write about apart from the small details. All those who bought these seven books may know about 95% of everything there is to know about the air war over Vietnam. The remaining 5% is what no Vietnamese and no American would like to talk about. They don’t like failure, you know. After one particular dogfight the Vietnamese claimed that one of their pilots had been shot down. After the war, when locals were asked about it, they said that one of the planes came in low over the village and crashed into a mountainside. But as he died in wartime, he is a hero, that is how the locals think about him.

Istvan Toperczer met these aces in 2013 in Saigon: they are looking at the photographs in the Osprey volumes identifying their former colleagues.

I'm planning to write a book about one particular pilot and his complete career. I have got a list of questions but that would take some time. Each subject should be interviewed for about a week, minimum. As I should talk with more than one pilot, that would mean about a month, total. Besides, talking about Asian people, it is very important to get close to them, first, and they open very slowly. It occurred that I mentioned some of my Hungarian pilot friends and it turned out they had flown together back in the Soviet Union: that made it all much easier.

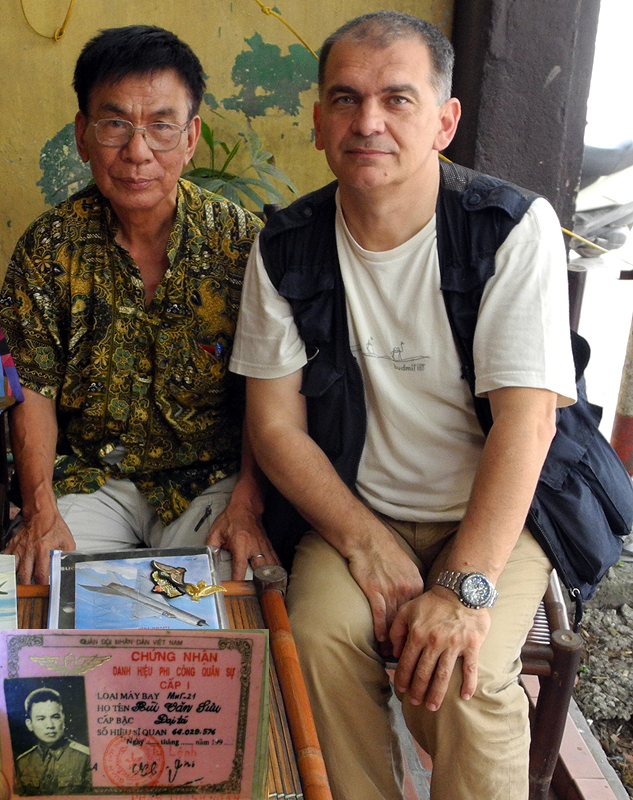

With Bui Van Suu, former MiG-17 pilot

Another thing is that their MiG-17 pilots were born around 1934-38 while their MiG-21 pilots around 1941-45. And more and more of them are gone now... Luu Huy Chao (1936), whom I met in 2013, unfortunately passed away one year later. Out of their MiG-17 aces only Nguyen Van Bay (1936) and Le Hai (1942) are with us, but Bay is very ill now and a bit unwilling to give an interview. Many of them were shot down in the war, others were killed in peacetime training accidents... And after 50 years, it is difficult to recount a dogfight. I read the battle reports countless times and I compared these to the interviews. I had to hasten the process and ask them until they could talk about their own viewpoint. What I tried to do is encourage them to share their own experiences.

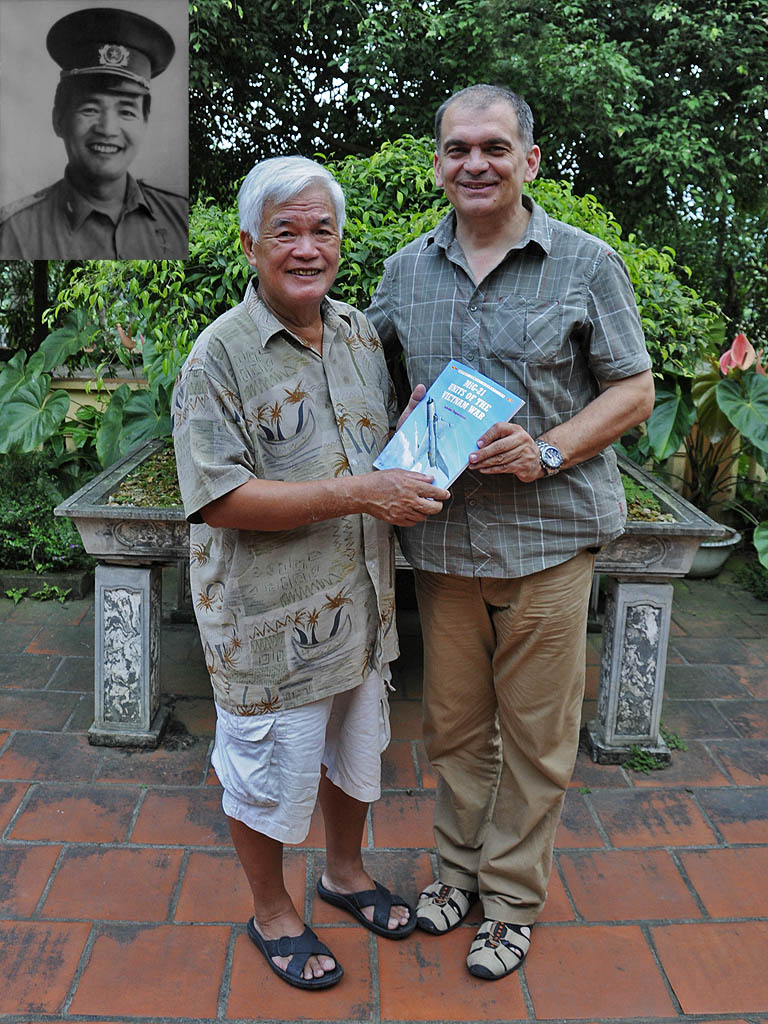

With Le Thanh Dao, former MiG-21 pilot

and an Osprey book he contributed to

One of these anecdotes is about Nguyen Van Bay. Maybe you know that these Vietnamese pilots were trained in a hurry. They were just able to be deployed and they really learned how to fly a fighter plane in wartime. It was Uncle Bay – as I call him – who told this story: his cockpit was damaged by gunfire during a dogfight. He just put his gloved hand there to cover the hole. He had not been very good at Physics, but the law of Bernoulli did work, and the pressure difference pulled out his hand in the blink of an eye... He learned it forever and I put this story into one of these books. All these stories can be compared to the American reports to re-enact a dogfight. Mistakes happened on both sides. Lots of questions arose about a certain event, a certain aerial victory... Maybe the American plane was smoking like hell, still, its pilot was able to bring it home. However, all the Vietnamese pilot saw was the enemy plane smoking and he confirmed the kill. There were contradictions on the American side, as well. One of them claimed he had been shot down by a 37 mm anti-aircraft cannon. Lest we forget, MiG-17s had a 37 mm cannon and these fighters launched their attack coming out from the mountains, like an ambush. The flights of American bombers flew in from Thailand; the Vietnamese MiG-17s, which were available in small numbers, were lurking behind the mountains, suddenly appeared, executed a hit-and-run raid, then disappeared. What did the Americans do? They dropped their bombs and turned their backs. For a while, they believed there was no Vietnamese Air Force whatsoever and so they did not prepare for such attacks. In the early days of the war dogfights were atypical; the Vietnamese launched these harassing flights. The Americans realised the threat of the Vietnamese MiGs and they sent escort fighters and Wild Weasels to seek and destroy radar sites. After 1967 and the introduction of the MiG-21 fighters, new tactics were needed on both sides...

In the home of Nguyen Hong Son, former MiG-19 pilot

As a kid, did you hear about the war? Did you follow the events?

I was at high school and when we left for home after lunch, we saw this huge mural painting at the bus stop: "HANDS OFF FROM VIETNAM!" I did not really understand what hand that was... That is all we knew, because we did not read the newspapers yet. Television newsreels featured war reports, but we did not really listen.

You've been all around the world. You are into photography and try to meet other cultures.

Originally, I wanted to be an archaeologist as I loved History. However, it was very difficult to get admitted to the Faculty of Arts. The father of a friend was a medical doctor. I liked what he did and so I became a doctor. I was still into archaeology and cultural history so I travel to places which were the cradles of civilization: Peru, Bolivia, the Incas; Central America: Aztecs, Zapotecs; Cambodia: Khmers; Sri Lanka, Ladakh; Buddhism. I went where I could touch History.

Group photo in the Vietnamese Air Force Museum in Saigon. Left to right: Tu De (former MiG-17 pilot who bombed Tan Son Nhut flying a captured American A-37 on 28th April 1975), Le Hai, Istvan Toperczer, Nguyen Van Nghia and Vu Ngoc Dinh.

What are your impressions about the Vietnamese people?

I love the country, I love the people. When they learn I am Hungarian, communication gets easier as the relations between our countries have always been good. Many of them studied over here, they returned to Vietnam and nowadays they are among national leaders. But even the average citizen knows about Hungary. However, more than 40 years passed since the end of the war. The middle-aged people of the Vietnamese society were born then, therefore they did not live through the war. Thanks to my books, I have several friends among them: as the books published by their military are unavailable, they read my publications to know the history of their air force. When I am out there doing my research, they help any way they can, like accommodation or transport. Last time one of my friends in Saigon told me it was an honour for him to come with me and meet a Vietnamese pilot he could normally never talk to. Sometimes they assist by acquiring some information and sending me via e-mail. By the way, personal computers are uncommon in Vietnam, they rather use their smartphones and Facebook. Many of their elder pilots use Facebook... When I send them a photo asking them to identify the colleagues in it, it might occur that I receive the answer in five minutes. It is so fast, I don't have to wait for months to get an answering letter. This is a huge help, especially when I am about to finish editing a book and the deadline is coming...

An old C-47 at Tan Son Nhut in Ho Chi Minh City (formerly Saigon). It served the US, then the South Vietnamese and the North Vietnamese Air Force. It is no longer serviceable.

Can you still find the remnants of the war in present-day Vietnam?

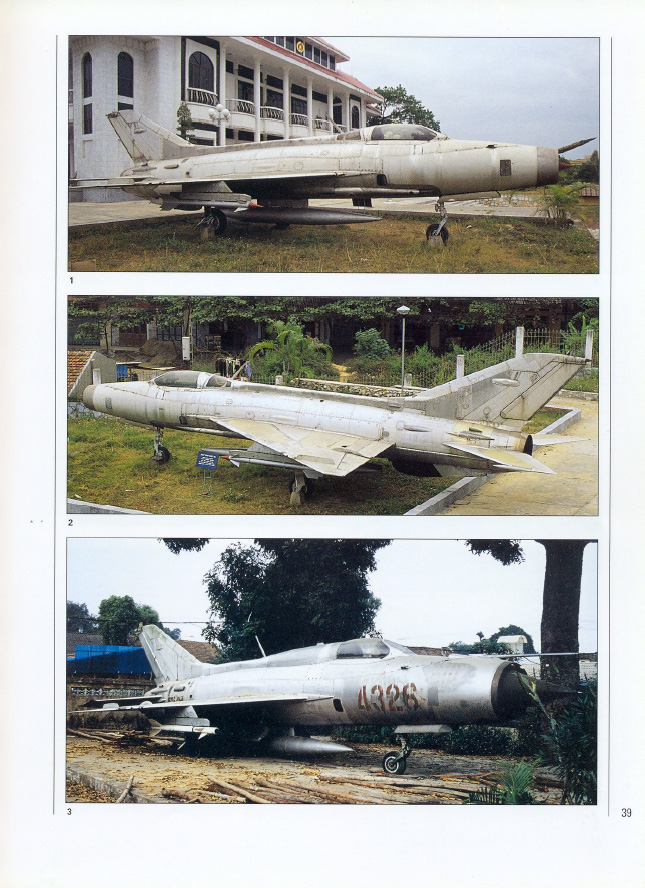

Well, the wreckage and the knocked out tanks have been cleared away from the roadside. These were taken to a furnace or are now exhibited in provincial or city museums. Back in 1994 I sometimes felt as if the war had just been ended. For example, I visited Khe Sanh and I found some dog tags, a poncho, American boots in the mud or a Budweiser beer can dated 1968. Locals had already collected everything they could use and left everything else. Selling souvenirs and landscaping began only years later. In those museums I saw MiG fighters and pieces of American planes, wreckage. I tried to find and photograph the ID plates or the name of the pilot on the fuselage. Apart from a few, I could identify the pilots and the stories of these planes. The photo materials featured in those museums have deteriorated since then. Most of the original pictures I collected back then are now useless due to the climate. Vietnam as a country is still much the same as it used to be. But the youngsters say those red-and-yellow, Socialist posters are hugely out-of-date by now...

Thank you for the interview.

A MiG-17 in the museum of Than Hoa. The Ham Rong bridge is situated nearby: the Americans were bombing it throughout the war as supplies were transported this way to South Vietnam. The first North Vietnamese aerial victories were scored above: two MiG-17s shot down two F-105D on 4th April 1965.